In recent years, the world has been starkly reminded of the interconnectedness of all life on our planet. From COVID-19 to Avian Influenza, a disturbing trend has emerged: most new infectious diseases in humans, an estimated 75%, originate in animals.

These are known as zoonotic diseases, and they represent a significant threat to global health security. But as we look to the future, can a seemingly niche field like veterinary science be the key to preventing the next great pandemic? The answer lies in a powerful, collaborative approach known as "One Health".

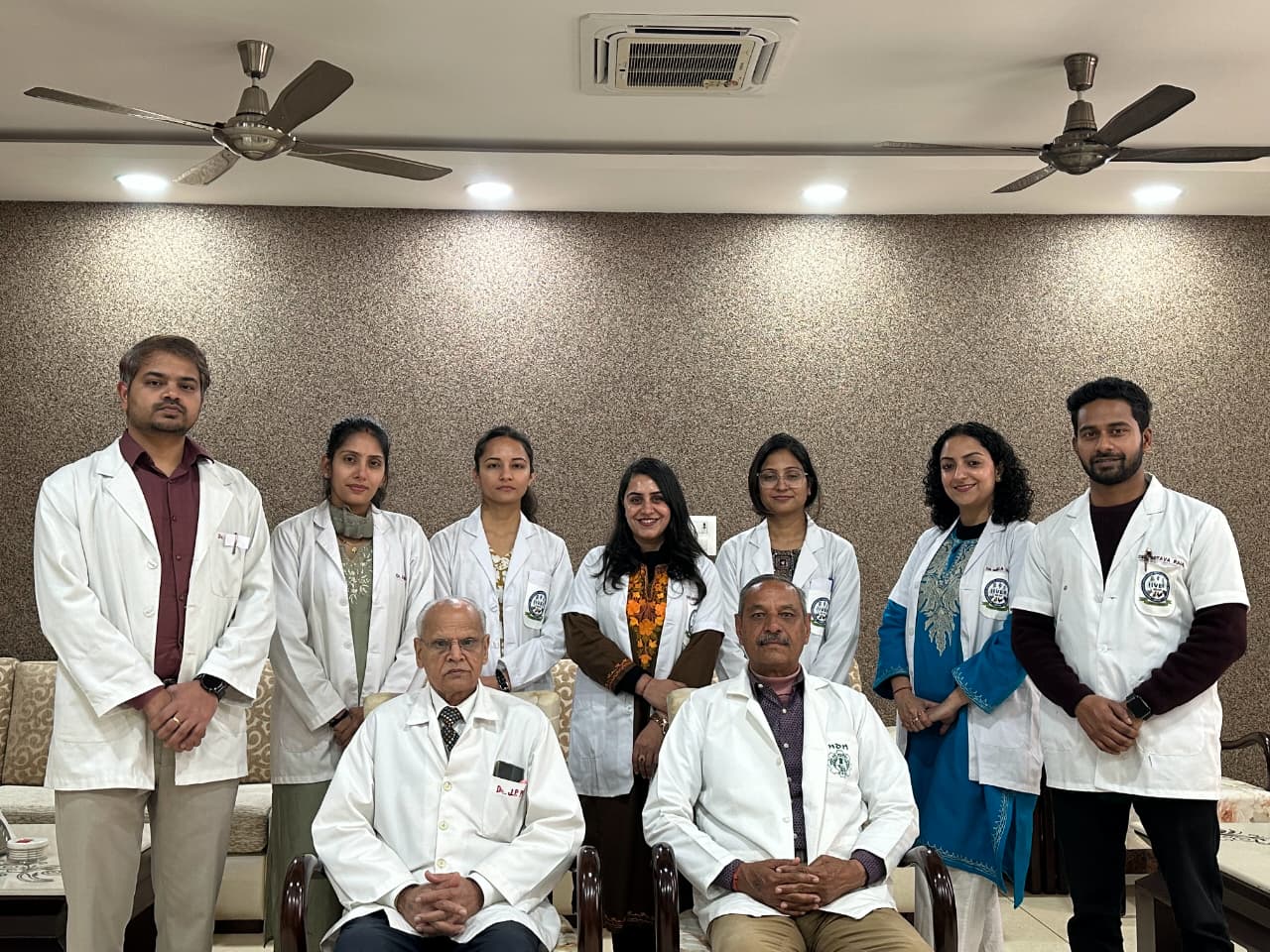

The Front Line of Defense: Veterinary Surveillance

Think of veterinarians not just as animal doctors, but as the first line of defense against emerging infectious diseases. They are uniquely positioned on the front lines, working with livestock, wildlife, and companion animals. Their daily work involves monitoring and reporting unusual disease patterns, which can serve as an early warning system for potential spillovers to the human population.

This surveillance is crucial. By identifying a new virus or bacterium in an animal host—before it has a chance to jump to humans—veterinarians can trigger a rapid response. This includes:

- Early Detection and Reporting: Vets are trained to spot clinical signs of emerging diseases and report them to public health authorities.

- Disease Investigation: They can trace the source of an outbreak in animal populations, helping to determine the cause and implement control measures like quarantine or vaccination.

- Biosecurity and Prevention: In agricultural settings, veterinarians work to establish and enforce biosecurity measures, ensuring the health of livestock and preventing the spread of diseases within farms and across borders.

The Power of "One Health"

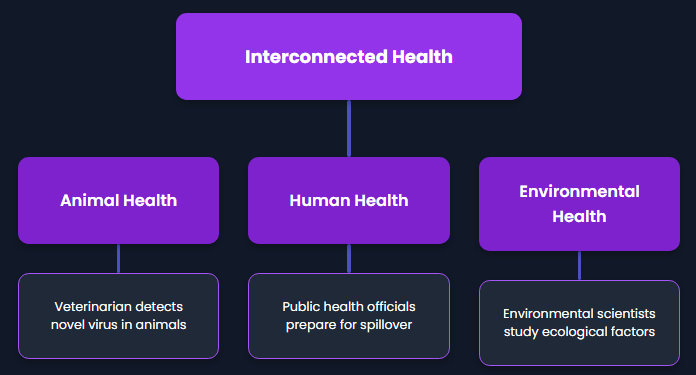

The true power of veterinary science in pandemic prevention is realized through the "One Health" approach. This concept recognizes that the health of people, animals, and our shared environment are inextricably linked. It's a call for professionals from different disciplines—physicians, veterinarians, environmental scientists, and public health officials—to work together to address complex global health challenges.

Instead of operating in isolated "silos," a One Health framework encourages a holistic, collaborative strategy. For a zoonotic disease, this might look like:

- Animal Health: A veterinarian detects a novel virus in a group of bats or a livestock herd.

- Human Health: Public health officials are immediately notified and begin preparing for a potential human spillover, developing diagnostics and public health campaigns.

- Environmental Health: Environmental scientists study the habitat and ecological factors that may have led to the virus emerging, working to mitigate risks like deforestation or habitat destruction.

This integrated approach is not just a theory; it has proven its effectiveness in managing past outbreaks like the Hendra virus in Australia and in ongoing efforts to control rabies. It's a proactive, rather than reactive, way to safeguard our world.

Success stories in action

Real-world examples demonstrate the critical impact of veterinary science and the One Health approach.

- Hendra Virus (Australia): In the 1990s, a new virus emerged in horses in Australia, causing severe respiratory and neurological disease. Veterinarians quickly identified the virus and its bat reservoir, working with public health officials to trace the outbreak and prevent a major human epidemic. Their swift action contained the spread and led to the development of a horse vaccine, protecting both animals and people.

- Rabies (Bali, Indonesia): When rabies re-emerged on the island of Bali in 2008, a collaborative One Health team was formed. Veterinarians, physicians, and community leaders worked together to implement a mass canine vaccination program and public education campaign. This coordinated effort led to a significant decrease in human cases and highlights how controlling a disease at its animal source is the most effective prevention strategy (Source: Federation of Veterinarians of Europe).

- Nipah Virus (Malaysia): In the late 1990s, a new virus causing severe disease in pigs and humans emerged in Malaysia. Veterinary teams traced the outbreak to pig farms, where the virus had jumped from fruit bats. Their efforts led to the culling of infected pig herds, which successfully halted the spread of the virus to humans, preventing a larger-scale pandemic.

India's proactive approach to One Health

India, with its dense human and animal populations and diverse ecosystems, is a key player in the global fight against zoonotic diseases. The country has proactively adopted and scaled up the One Health approach, with several initiatives demonstrating its commitment.

- National Animal Disease Control Programme (NADCP): This government-led program is focused on the eradication of diseases like Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD) and Brucellosis, both of which have significant economic and public health impacts. By vaccinating millions of livestock, the program directly prevents the spread of these diseases from animals to humans, safeguarding both food security and public health.

- National Animal Disease Reporting System (NADRS): This web-based system acts as an early warning network, linking veterinary field workers to a central database. By enabling rapid reporting and monitoring of livestock diseases, it allows for swift preventive and curative action during disease emergencies. This system is a prime example of how digital infrastructure strengthens a One Health framework.

- Strengthening Animal Health Systems: In recent years, India has launched projects like the "Animal Health System Support for One Health" and the "Animal Pandemic Preparedness Initiative," funded in part by the World Bank. These initiatives aim to improve veterinary infrastructure, enhance disease surveillance (including genomic and environmental surveillance), and build the capacity of animal health professionals across the country.

- Kyasanur Forest Disease (KFD): Also known as "Monkey Fever," this tick-borne viral hemorrhagic fever affects communities in southern India. A One Health ecosystem approach was used to understand and mitigate the disease's spillover from ticks and monkeys to humans. This collaborative effort brought together veterinarians, public health officials, and environmental scientists to manage the disease at its source.

How can students contribute?

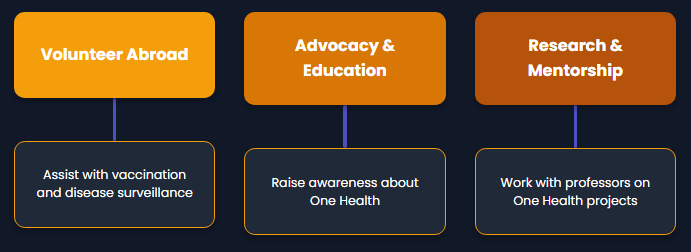

Students, particularly those studying veterinary medicine or public health, are not just future professionals—they are a vital part of the solution right now. Getting involved early can provide invaluable experience and strengthen the global One Health network.

- Volunteer Abroad: Organizations like Veterinarians Without Borders and Worldwide Vets offer volunteer opportunities in developing countries. Students can assist with vaccination clinics, spay/neuter programs, and disease surveillance, gaining hands-on experience with diseases not common in their home countries.

- Advocacy and Education: Become a One Health advocate. Join student clubs, write for school publications, or use social media to raise awareness about the link between human, animal, and environmental health. You can educate your peers and the public about the importance of biosecurity and the risks of zoonotic diseases.

- Research and Mentorship: Seek out opportunities to work with professors or researchers on One Health projects. This could involve laboratory work, data analysis, or field studies. Building relationships with professionals in the field can open doors and provide guidance for a career dedicated to pandemic prevention.

Conclusion

So, can veterinary science prevent the next zoonotic pandemic? It is a crucial, non-negotiable part of the solution. By leading the charge in surveillance, disease investigation, and food safety, and by championing the indispensable "One Health" approach, veterinary professionals are not just protecting animal well-being—they are serving as vital guardians of global public health. The greatest threat we face is not a lack of scientific knowledge, but a failure to recognize and invest in the interconnected web of life that sustains us all.